While society is slowly coming to grips with the idea (and consequences) of cultural appropriation –when a person from a dominant culture takes over and reproduces the codes of a minority culture–, emotional appropriation is a new kind of theft that has been making waves online. Emotional appropriation is when one appropriates emotions that aren’t their own, and it’s an issue that is being propagated on the Internet consciously or unconsciously via our use of emojis and GIFs.

A brief history of the Internet

Getting your emotions across on the Internet or via any medium of online communication is a tedious affair, as these platforms are devoid of affect. It’s for that reason that developers came up with the idea of emoticons at first, leading to emojis and GIFs later on, as mediums to express our emotions by replicating the non-verbal elements of communication online. And so, the smiley face : – ) and the winky face ; – ) were born in the 1980s out of this a lack of understanding of other people’s tones of voices on online forums.

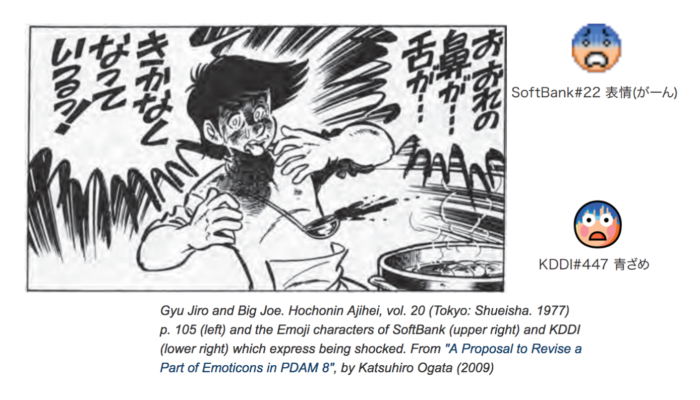

Its successor, the yellow smiley face or emoji, appeared the next decade in Japan, inspired by calligraphy, ideograms and manga culture. In fact, when the first iPhone came out in 2007, emojis were intended to attract the Japanese market.

Since then, emoticons, emojis and GIFs have become ubiquitous to our online –and sometimes offline– exchanges, to the point that Oxford Dictionary’s 2015 word of the year was the crying tears of laughter emoji 😂(the most used emoji globally in 2015), because “it best reflected the ethos, mood and preoccupation of 2015”. This testifies to the power of the emoji to expand and redefine the vocabulary of emotions.

The emoji, a symbol of dominance?

The emoji is both a digital and cultural phenomenon. One’s use of emojis reflects one’s culture, as revealed by 2015 study by Swiftkey. It explained that the two most popular emojis that year, the peach and the aubergine, were particularly used in more conservative countries such as English, Canada and the US while the French, use the red heart emoji four times as more as any other country, a reflection of their Latin romantic traditions, as analysed by the Guardian writer Arwa Mahdawi. Australians send the beer emoji twice as much compared to other countries, while in Brasil, a mostly Catholic country, the praying hands and church emojis ranked high.

However, what this study also reveals is that the most popular emojis across the world are also emojis that reflect the most dominant cultures. This can be explained by the late arrival of certain emojis on the market, like the hijab emoji which appeared 10 years after the very first emoji or the natural afro hair emoji, reinforcing the fact that minorities have less of a voice online compared to dominant cultures.

GIFs and emotional appropriation

If emojis reinforce cultural dominance, so do GIFs… In the US, the most used GIF to express happiness is of Oprah Winfrey shouting with excitement. Second is Fresh Prince of Bel Air character, Carlton dancing. The GIF to express anger? Beyoncé in her Lemonade music video swinging a baseball bat around.

The issue this raises is that these GIFs are not only being used by people of colour, and are in fact mostly being used by non-black people. People of colour, in particular women of colour, are being called on very frequently to express the emotions of non-black people, bringing blackface into a new dimension: the digital realm.

Blackface happens when a non-black person paints their face black. It is a racist practice that started in the 19th century with minstrel shows, a theatrical tradition in which white performers would blacken their skin to caricature black people. This racist behaviour remains alive and thriving in certain communities, and is also unconsciously being perpetrated by celebrities today –French football player Antoine Griezmann dressed up as an NBA player and model Gigi Hadid was also accused of blackface on the cover of Vogue Italia.

Using a GIF of a black woman when you’re a white may not seem like such a big deal compared to this racist Jim Crow era practice, but the excessive use of GIFs representing black people, testifies to a deeper problem in society: black people are overrepresented online but underrepresented elsewhere.

As journalist Lauren Michele Jackson points out in Teen Vogue, “our culture often associates blacks with excessive behaviour, regardless of the behaviour in question. Black women will often be accused of shouting when we have not raised our voice so much.”

Digital blackface can thus be akin to emotional appropriation, however, as with many cases of cultural appropriation, it often does not come from a bad or disrespectful place, but it does not mean it does not hurt the people and peoples whose emotions are being stolen from them.

Black culture is not only being appropriated through images but also language. Phrases like “Bruh”, “Oh no you didn’t”, “Yaaaas” or “Bye Felicia” are being used by non-black people, in particular on Twitter. This leads to what Manuel Arturo Abreu calls “online imagined black English”. As he explains, “in recent decades, the advent of hip-hop and the internet have arguably spread black media farther than ever before.” This is something theorised by Cecilia Cutler, who explained that hip-hop is becoming an increasingly multi-cultural lifestyle rather than the symbol of an ethnic group, “from which white teenagers can selectively choose to construct their stereotypes about African Americans and hip-hop culture.”

Taking into consideration the racist historical context, the case for emotional appropriation in a time of #BlackLivesMatter brings to the forefront issues of cultural dominance. Non-black people rely on black people and black images to express emotions for them, making black people perform an important task of emotional labour on their behalf.

What can and should be done?

The solution is not to stop circulating an image that represents someone from another race, but be wary and conscious of the content that we share and the context in which we share it. The Internet is a reflection of societal tensions, not a faraway fantasy land that’s devoid of political, social, cultural, emotional injustices. If the first ten GIFs the platform suggests aren’t appropriate, scroll further. The power of suggested content is strong; there’s a strong chance that if the social media suggests to its user to send GIFs representing people that don’t reflect their race, there’s also a strong chance that’s what the user will do. It’s not only up to the user to make a conscious choice to look beyond the first results, but the responsibility is also in businesses’ hands.

As from a marketing viewpoint, marketers will need to be careful in their use of images and language to make sure they avoid not only cultural appropriation –as exemplified by the Dove and H&M’s fiascos– but also any sort of emotional appropriation.